tags:

Bridger Wilderness, WY |

wyoming |wind rivers |wind river range |wilderness |titcomb basin |tgr news |story |shingo ohkawa |rock climb |photography |oli shaw |mistake lake |mark evans |landscapes |fremont peak |first ascent |exploration |eagle's nest |creativity |climbing |bridger |adventure

“Hardest mountain, Haaaaardest mountain.”

A soft tune wafts into the crisp mountain air. Mark is walking ahead of me on the trail while he sings a self composed tribute to the landscape in front of us. He makes no effort to restrain his devotion to the scraggly granite peaks lining the horizon and flings his arms outward, as if trying to embrace all the giants at once. As I watch Mark’s gestures, I notice the colors and shades of the landscape changing. The glow from the landscape isn’t just coming from a setting sun, it’s also pouring over from an unrestricted sense of human creativity and expression. Even as the sun continues to set I feel, with each step towards the mountains, an increasing intensity of light washing over me.

Somewhere past a fluttering tarp strung up between a few pine trees a voice invites us in: “welcome to the Crow’s Nest.” I follow my friend past neatly stacked boxes of cookware, food, alcohol, and climbing gear into an opening where a group of people are sitting in circle. My friend and I are both relieved to hear the invitation and we quickly offload our overstuffed backpacks. One person in the group makes space for me to sit on his sleeping mat and offers me a sip of coffee. “I’m Oli,” he introduces himself, “and the person sitting next to you is Mom.” I shake both of their hands and somehow feel at home amidst complete strangers.

When I first walked into the Crow’s Nest I had no idea what I was going to find. Just the day before, I had received an email from a good friend asking whether I wanted to join him on a last minute trip into Wyoming’s Bridger Wilderness. My friend, Ben Ramsey, a journalist for a local newspaper in town, was hoping to write a story about a group of climbers who were setting a new route on one of the tallest peaks in the Wind River Range. Beyond the idea for a trip and a story, he had no clear information on the whereabouts of the climbers or when they would be attempting their climb. I agreed anyway. I didn’t need a better reason to spend the weekend outside with a friend. We hit the trail that same evening.

A night underneath the stars and twelve miles later we managed to spot the Crow’s Nest. My skepticism about how welcoming the group of climbers would be to someone they barely knew was shattered the instant I sat down next to Oli and his mother. In no time, we were sharing shots of whiskey – courtesy of Ben who had courageously hauled an entire bottle up the trail – and laughing uncontrollably at terrible jokes. My friend had even less trouble fitting in with the group - at some point I found Ben hurling himself off a cliff along with another climber, Jake, into the frigid waters of a glacial lake.

Jake sips from the Famous Grouse. Any swig from the bottle had to be accompanied by a mock grouse call. We all agreed that Jake’s mimicry was the most accurate.

Ben and Jake take an epic swim in Island Lake.

“It feels more real out here,” Shingo Ohkawa, the organizer of the climbing expedition, tells me while we are sitting around at the Crow’s Nest. We are deep into a conversation about our shared heritage and connection to Japan when Shingo begins revealing his true motivations for climbing. “Back home there are a lot of distractions and I feel like it’s so easy to get caught up in the really small obligations of everyday life. Life is much simpler when I go out climbing.”

Eat, sleep, hang out, and climb. Being in the wilderness and climbing requires one to really focus on the most fundamental and important aspects of life.

The simplicity also brings people together. People who otherwise have very little in common back in the ‘real world’ have to contend with the same challenges in the wilderness. Students from MIT, a hiker seeking shelter from a rainstorm, the parents of climbers, not to mention a journalist and a photographer are among those who’ve shared the same space and time underneath the blue tarp of the Crow’s Nest. Out here there are few strangers.

Several hours go by at the basecamp and the sun begins to lean heavily towards the west. Just after dinner, Shingo assembles the team that will be heading the expedition to establish a new route up Fremont Peak, the primary objective of the trip. Three climbers, Shingo, Mark Evans, and Oli Shaw will be attempting the climb tomorrow. Everyone at the Crow’s Nest wishes them luck as they head off to spend the night in a bivouac near the base of the cliff. Before I even have time to assemble my pack, the climbers are off. I have to run to keep up with them as they speed up the mountainside.

Mark and Shingo make their way into Titcomb Basin where they will spend the night at a bivouac site just below Fremont Peak.

Not long after I arrive at the bivouac exhausted, struggling under the weight of my gear and out of breath from the lack of oxygen at nearly 12,000ft in elevation. Despite the pain my spirits are high. I feel more overwhelmed by what I’m seeing in front of me. “This is a really special place. Not that many people get to see it,” Shingo shares. His thoughts are the same as mine.

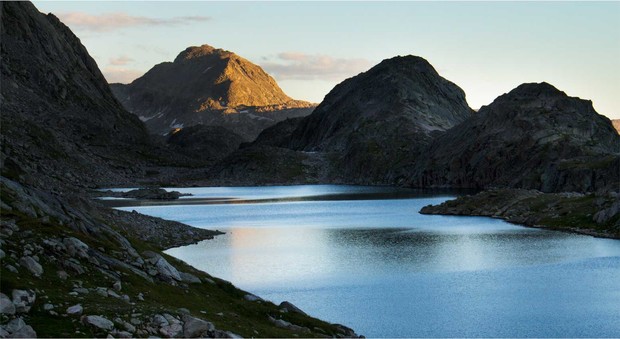

Our bivouac is nestled up against a giant boulder that juts out from the slopes leading up to the massive walls of Fremont. Below us are a series of glacial lakes ringed by the jagged mountaintops of Titcomb Basin. Each lake punctures the dark silhouettes of the mountains with a piercing reflection of the deep blue sky. Intermittently, a peak catches the final embers of a fading alpenglow and radiates the light down into the basin. We spend several moments watching the spectacular light show cascade over the mountains.

Incredible views from our bivouac. Mistake Lake in Titcomb Basin reflects the glow of the evening sky.

In the background, Mount Lester catches the final light of a setting sun.

As nightfall plunges Titcomb Basin into a deep darkness, the climbers begin to turn their focus on tomorrow’s climb. Shingo runs through the game plan with the other two climbers: “we came here to climb this peak, so let’s not let a few clouds hold us back.”

Twice already, the notoriously temperamental weather patterns of the Wind River Range had kept the team from reaching the top of Fremont Peak. Last year the crew spent two weeks waiting at basecamp for a break in the rain – they never got the chance to climb. This year, the climbers had been driven off the cliff by a freak snowstorm. They were no more than one hundred feet from their destination when they were forced to turn back. Tonight the climbers vowed to push through; and judging from the utter silence of the wind, it seemed like, for once, the sky would be willing to let the climbers reach their destination.

Mark and Shingo get ready for a night underneath the stars. The new route on Fremont peak looms above the two climbers.

Mark relaxes before tomorrow's big climb

At some point in the night I wake up. Curious about the weather, I peer out of the narrow opening in my sleeping bag. Above me, a vast expanse of darkness, interrupted only on occasion by glimmering points of light, stretches out to the horizon where it meets the saw-tooth peaks of the Wind River Range. The air is completely silent. No one else in the bivouac stirs.

The utter calm of the night is reassuring. This is the best chance the climbers have to make it to the top and I’m sure they will pull it off tomorrow. With that thought lingering in my head I close my eyes, settle back into the pile of rocks underneath my sleeping back, and slowly drift off to sleep.

Fremont Peak illuminated by the moon and the stars. Tomorrow morning Shingo, Mark, and Oli will set off to scale an uncharted face of the second tallest peak in the Wind River Range.

Five in the morning comes early the next day. A quiet and muffled commotion next to me tells me it’s time to get going. Oli whips up a pot of blueberry oatmeal and coffee and we all wash it down. Just as the first rays of light begin peering over Fremont Peak, the climbers assemble their gear and begin working their way up the mountainside. I hastily pick up my pack and camera, try to shake off my morning drowsiness, and once again scramble after the climbers who are quickly disappearing up the talus slope.

By the time I reach the climbers, they are already in the final stages of preparing for the climb. They work silently and methodically: ropes, cams, and carabiners are neatly laid out and harnesses, helmets, and packs are securely fastened. As I watch I feel as though I’m witnessing an ancient ritual being performed in a sacred place. Each quiet movement is a gesture of devotion and respect for the incredible scenery surrounding us on all sides.

The climbers perform their final ritual before beginning the ascent. Shingo looks up with determination at the top of Fremont peak.

At the conclusion of the climbers’ ritual Shingo turns to me and gives me a big hug. “Thanks for joining us this far.” From this point forward, Fremont Peak juts up straight into the air and the climbers will proceed upward without me. I thank the guys for their hospitality and their willingness to invite a complete stranger on their adventure. I’ve only known Shingo, Mark, and Oli for less than a full day and I feel like I’m saying farewell to close friends.

Not long after we say our goodbyes the climbers turn into tiny specs on a massive wall of granite. I let the wind carry away my wishes of good luck up to the climbers before turning around to begin the long descent home. The hike back down is tough: I’ve burnt through most of my energy chasing after the climbers and the adrenaline that has so far helped mask my exhaustion is now completely spent. I have to force my body to make each step on the fifteen mile hike back to the trailhead.

As I made my way back home, one of Shingo’s parting statements kept reverberating in my mind: “I always miss the moments when we are hanging out and are able to freely express ourselves.” I was certainly going to miss hanging out with friends at the Crow’s Nest, but I also felt like I was walking away with something meaningful.

Deep in Wyoming’s wilderness I had witnessed a convergence of passions: climbers exploring the limits of their strength and creativity on an unexplored route, a journalist relentlessly pursuing a challenging story, a photographer patiently crafting images that articulate the beauty of people engaging their world. Our combined creativity had ignited a hunger for life inside of me that had previously laid dormant. I knew that while I would be leaving behind good times at the base of Fremont Peak, I was pulling myself towards an even greater desire to express more of what I saw in the world and in other people. I wasn’t just walking home with a handful of good memories: I was walking out into a landscape where I was shining just as brightly as everything and everyone else around me.

Seven hours after we part ways, Shingo, Mark, and Oli reach their destination. Their new route on Fremont is named “They Live.”